Englishmen in

the Confederate Service

Many

Englishmen played active roles in the Confederacy. Their loyalty resulted from

having similar beliefs with American Southerners, who were often their neighbors

in the more cosmopolitan southern cities like New Orleans. Their active

participation in the army was encouraged by the South, as demonstrated in this

excerpt from an 1863 article printed in the Richmond Examiner newspaper.

“Wherever and whenever a war for freedom is given, there Englishmen will be

found, not for glory only, but for the natural bull-dog love of fighting and the

inborn British love of the just cause and the weak side. … We bid the

Anglo-Confederate comrades God speed, good luck, and plenty of promotion, for

they are sure to deserve it. And if they are disposed to settle down in Dixie,

we have no objection to their forming an alliance with some of our pretty

Southern girls.”

Francis W.

Dawson, age twenty, was one such Briton who, after reading about the war in

British newspapers, decided to join the Confederacy. “ I had a sincere sympathy

with the Southern people in their struggle for independence, and felt that it

would be a pleasant thing to help them to secure their freedom. It was not

expected, at the time, that the war would last many months, and my idea simply

was to go to the South, do my duty there as well as I might, and return home to

England.” However, this would not be proven the case for many British

subjects offering their help to the Confederacy. Like thousands of Southerners

who signed up with the Confederacy for “the duration of the war,” British

volunteers were caught up in the deadly world of warfare for four long years.

However, this hardship did not dull their enthusiasm for the cause in which they

believed. In a letter written to his mother in 1862 Dawson explained, “You may

be rest assured that [as long as] one of [Britain’s] children has the power to

wield a sword or pull a trigger, the South will never desist from the struggle

against the northern oppressor. The bitter, bitter hate with which the name of

Yankee is received here, and the deep-rooted contempt with which every thing so

called is met, would be sufficient proof that the conquest of the Southern

Confederacy must be nothing short of annihilation.” Dawson’s beliefs in

the Confederacy were so strong that he refused to compromise them even at the

end of the war. “As an officer of Robert E. Lee’s Army, although not present at

the surrender, I was entitled and received my parole. I am now on parole and

not allowed to leave the country. I could cancel the parole and free myself

by taking the oath of allegiance to the United States Government, but this I am

not willing to do, so as soon as a British Consul comes to Richmond, I shall

endeavor to obtain protection as a British subject.”

Colonel

Arthur Fremantle of Great Britain’s Royal Army was the best known British

subject who wrote of and published his experiences with both the Union and

Confederate armies in his role as an “observer.” He wrote about his feelings

over the conflict in the preface of his book entitled, Three months in the

Southern States. His comments may reflect not only similar feeling among his

countrymen at the time, but may explain why historians and the general public of

today continue to be mesmerized with the American Civil War. “At the

outbreak of the American war, in common with many of my countrymen, I felt very

indifferent as to which side might win; but if I had any bias, my sympathies

were rather in favor of the North, on account of the dislike which many

Englishmen naturally feels at the idea of slavery. But soon a sentiment of great

admiration for the gallantry and determination of the Southerners, together with

the unhappy contrast afforded by the foolish bullying conduct of the

Northerners, caused a complete revulsion in my feelings, and I was unable to

repress a strong wish to go to America and see something of this wonderful

struggle…fore I think no generous man, whatever may be his political opinions,

can do otherwise than admire the courage, energy, and patriotism of the whole

population, and the skill of its leaders, in this struggle against great odds.”

Thomas E. Williams

England

had strong ties with the South, as it needed the South’s valuable cotton for its

textile industry. Although England had abolished slavery in its homeland in

1815, it understood the use of the institution in the agriculturally based

South. Many British-born subjects and first generation siblings living in the

city of New Orleans had similar beliefs and joined the Confederacy. They viewed

the South’s secession from the Union very similar to that done by the United

States from England in 1776.

Britons and their

first generation American-born descendants also joined the Washington Artillery.

Thomas E. Williams was one such example. His parents had migrated to America

from England and settled in New Orleans. Williams grew up there and developed a

strong bond and loyalty to his Southern birthplace.

Thomas E.

Williams did not join the Washington Artillery in New Orleans but instead chose

the 18th Mississippi Volunteers on April 29, 1861, while employed in

Mississippi. He was elected Second Lieutenant of Second Company.

Ordered to Virginia with his unit, he saw action in the Confederate victories at

Manassas and Ball’s Bluff, Virginia. Williams was appointed Adjutant of the 6th

Battalion of Mississippi Volunteers Department of the Mississippi on June 14,

1862. However, on August 23, 1862 while stationed in Vicksburg, he requested a

transfer to and was accepted into the Washington Artillery, dropping in rank to

private. This request was officially granted by order of Brigadier General S. D.

Lee on December 3, 1862. His transfer papers to the Second Company Washington

Artillery listed him as born in Louisiana, 25 years of age, single, 5’8” tall,

light hair and complexion, and with the occupation of “soldier.” The reason for

his transfer is uncertain. He may have desired to transfer to a New Orleans

unit, especially one with the credentials of the Washington Artillery, which he

observed at the battle of Manassas. But his reason may have also arisen due to a

different motivation. An official document dated March 10, 1863

concerned his request for back pay and “bounty” for joining the WA. This

suggests that the transfer was, for one reason at least, monetary.

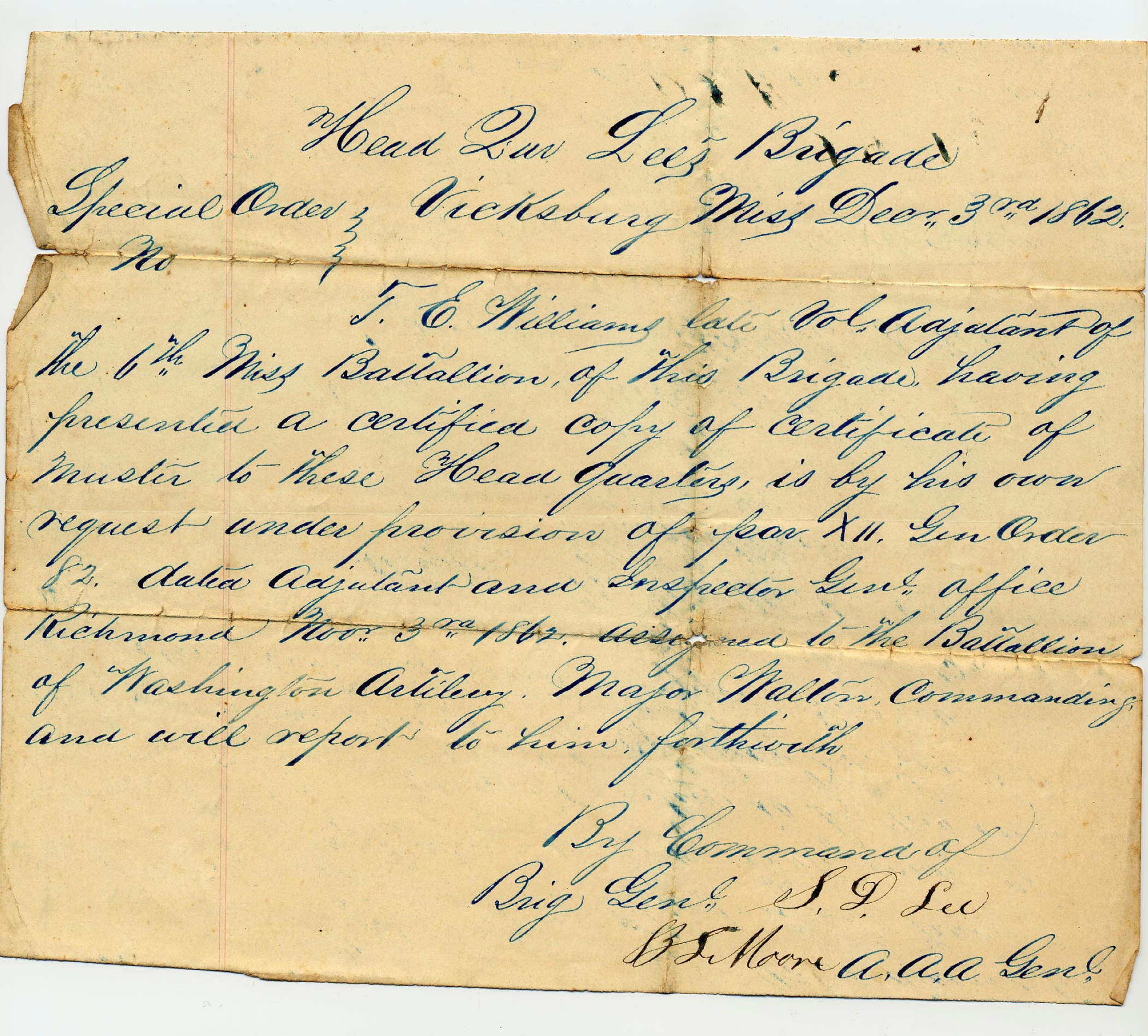

Transfer orders for T.E.

Williams signed by General S. D. Lee

The same day of

Williams’ acceptance in Mississippi to the Washington Artillery, his newly

adopted Second Company was engaged in a hot battle over the Rappahannock River

in Virginia. By the time Williams finally caught up with the WA he was able to

participate in the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. In the latter

battle he was wounded while performing his duty during the July 3rd

artillery duel. T. E. Williams was present during the great siege at Petersburg,

Virginia in 1864. He managed to survive the war, even refusing to surrender at

Appomattox, running into the hills with other WA members. He surrendered later

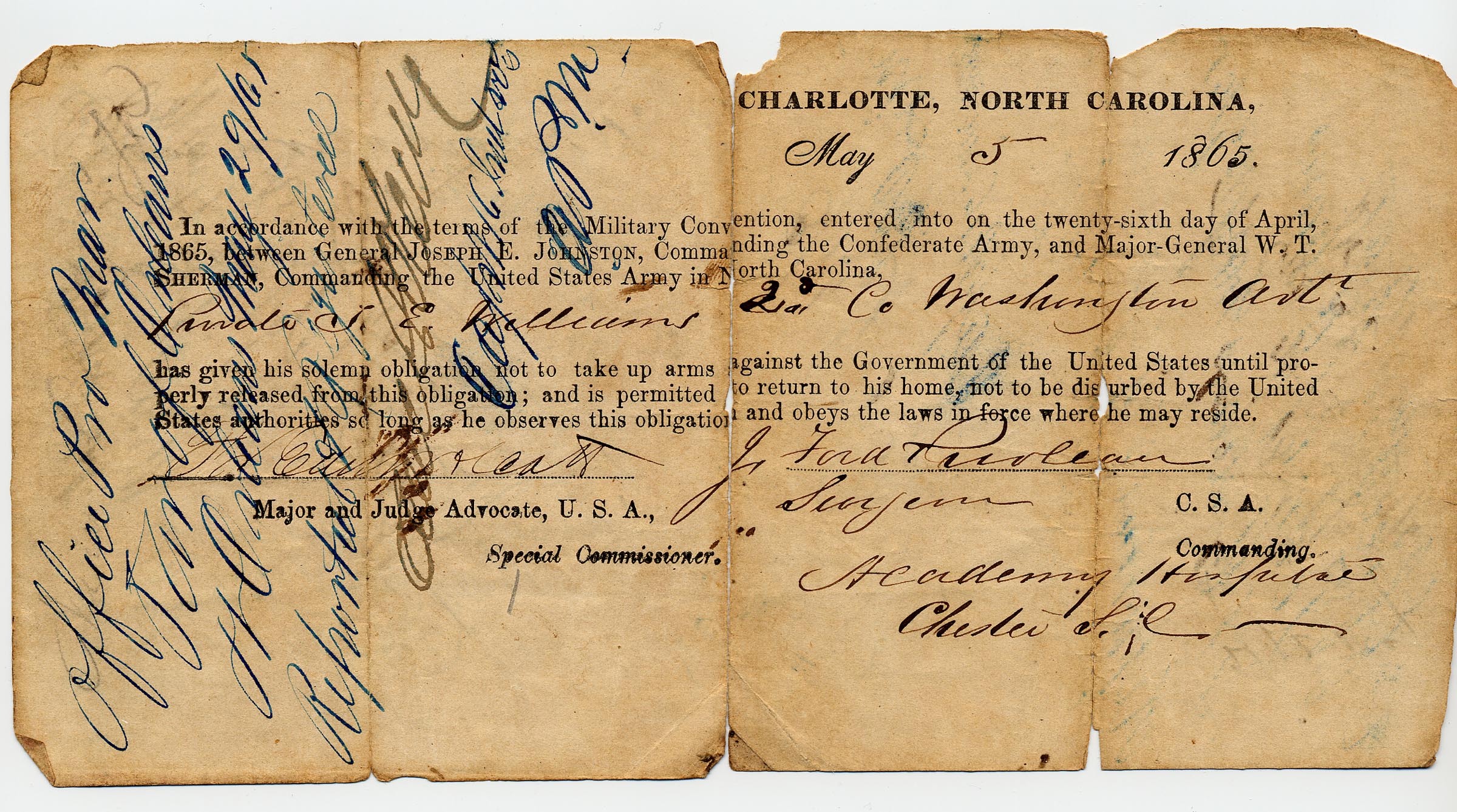

at Charlotte, North Carolina on May 5, 1865.

T. E. Williams' Parole

He returned to

Louisiana, married, and settled in Madisonville, north of Lake Pontchartrain. He

died on February 27, 1872 at the young age of 34. His funeral procession left

his home on 515 Royal St, corner of Lafayette Ave, and terminated with services

held at his Masonic Lodge #102. (Daily Picayune 2/28/1872,p.4, col. 6)

The battalion had one

other British New Orleanian named “Thomas Williams” who saw action with the 5th

Company as a driver, but he was discharged on January 19, 1863 at his request as

being a British subject. Tired of fighting but loyal to the cause, he remained

with the company as Captain Slocomb’s personal attendant. He was present with

that unit’s surrender at Meridian, Mississippi on May 10, 1865.

HOME