Let There Be Music!

Music of the Washington Artillery

“I don’t

believe we can have an army without music.”

Robert E. Lee 1864

There are numerous

examples of how music is a part of the Washington Artillery. During the 19th

century, the unit marched off to war in 1861 with the gala of pomp and

circumstance and still managed to incorporate music into their camp life

throughout the war in order to combat the stresses of military life.

From the very beginning of the war the men of

the Washington Artillery tried to maintain their reputation of culture and

compassion they originated in New Orleans. In a letter written home to the New

Orleans newspaper Crescent dated August 1, 1861, a member of Wheat’s

Battalion in Virginia wrote “August 24, 1861, the Washington Artillery in New

Orleans turned over $1280 as the result of a concert given to assist destitute

families.”

Henry H. Baker of 1st

Company wrote about the temperament of the unit in his post war booklet, A

Reminiscent Story of the Civil War. “No matter whether it rained or snowed,

the boys of the Washington Artillery, as a body, were unflinching, and no amount

of discomfort or hardship could break their spirits. Often when it was pouring

rain and the roads were deep with mud, the army would look with amazement as the

boys would pass along the road with a swing and dash so characteristic of them,

wet to the skin, singing one of their rollicking camp songs.”

Frank Labrano of First Company wrote in his

diary on September 10, 1862, “It was a clear day, reveille at 31/2 AM. Took up

our line of march at 8 AM, passed through Frederick at 9 AM, and by request of

Longstreet, the boys sang “My Maryland” and other patriotic songs passing

through town.”

Their artistic skills were exhibited throughout

the war. They performed numerous performances of theater for both Southern

troops and civilians. At Petersburg Bartlett commented that “the amateur

performers gave entertainment – ‘Pocahontas’ and ‘Toodles’ - in the theatre of

the town, which drew a packed house, ladies not only from Petersburg, but

Richmond.” These talents came in handy to counteract the boredom of idle time

often found in winter quarters, which could be dangerous for the men’s morale.

All companies of the Washington Artillery loved

the art and past time of song even during the most trying times. One example of

the 5th Company’s coolness under fire occurred in Georgia. During the

Federal bombardment of Atlanta, enemy shells were bursting throughout the city

as it marched through. Suddenly Pvt. Louey Vincent, reared back in his saddle

and belted out a familiar tune at the top of his voice, “The watch dog is

snarling, For fear that Anne darling, My own true love, this night, be borne

away!” Then the entire company responded with the chorus, trying to drown out

the sounds of exploding ordinance.

Frank

McElroy of First Company was probably the most famous singer of the battalion.

He was described by Bartlett as “the lively and jovial man of the Battalion, and

probably never suffered a day from mental depression during the war. He had an

excellent voice, and there were but few towns in General Lee’s line of march

which were not made familiar, through him, of old New Orleans fireman choruses.”

But

the most famous tale of song involved the 5th Company in the trenches

around Jackson, Mississippi. The unit had taken a defensive position there

following the fall of Vicksburg in 1863. With the approach of Federals on July

the 11th the 5th Company opened fire on the enemy, which

was repulsed with heavy losses. During breaks in the engagement members of the 5th

Company, with bugler Andy G. Swain leading, sang and taunted the enemy with

their tunes. A piano, commandeered by members of McPeely’s Louisiana Pioneer

Company from a Confederate civilian’s house at the request of its owner prior to

the house’s destruction, was put to good use by members of the Washington

Artillery, singing “You Shan’t Have Any of Our Peanuts!” Between songs

one of their Federal prisoners, a wounded officer, asked them, “How can you do

so, when so many of your fellow men are dying all around you?” A sharp answer

was replied, “How can you come down and invade our homes and make war on

defenseless women and children?” The singing resumed.

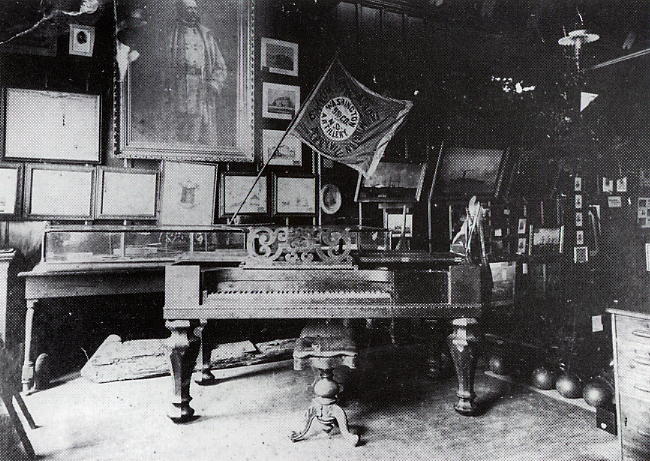

Piano used by the Washington Artillery in the Trenches

of Jackson, Mississippi

(Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, New

Orleans)

According to Mr. William Hirian Duff, a veteran

of the 16th and 25th Louisiana Consolidated Regiment,

members of Company B, McPheely’s Louisiana Pioneer Company, of which he was a

member, was sent to protect an abandoned house from looting outside Jackson,

Mississippi in 1863. Unfortunately, the house was ordered leveled in order to

prevent Union sharpshooters from using it as a vantage point to fire into

Confederate lines. The lady of the house appealed to McPheely’s Company to save

her piano which they did, carrying it back to the Confederate trenches. On their

return from burning the house down, they found the piano put to good use by Andy

Swain of the 5th Company Washington Artillery.

In 1902 children of the

owner of that house and piano, William A. Cooper, donated the historic piano to

Memorial Hall museum in New Orleans, where it stands and is used still today.

(William H. Duff, “The Truth – A Piano in

Confederate Trenches”)

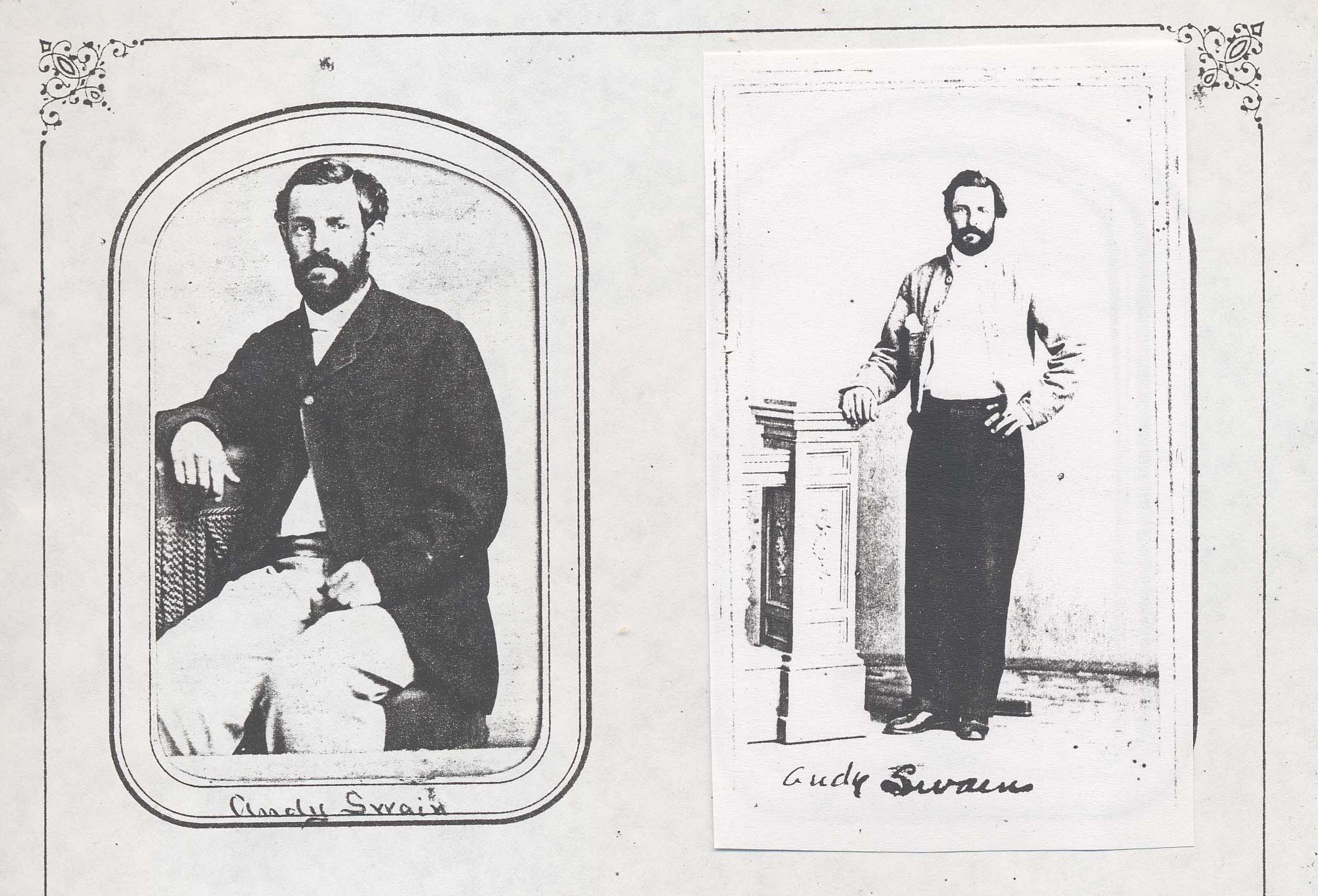

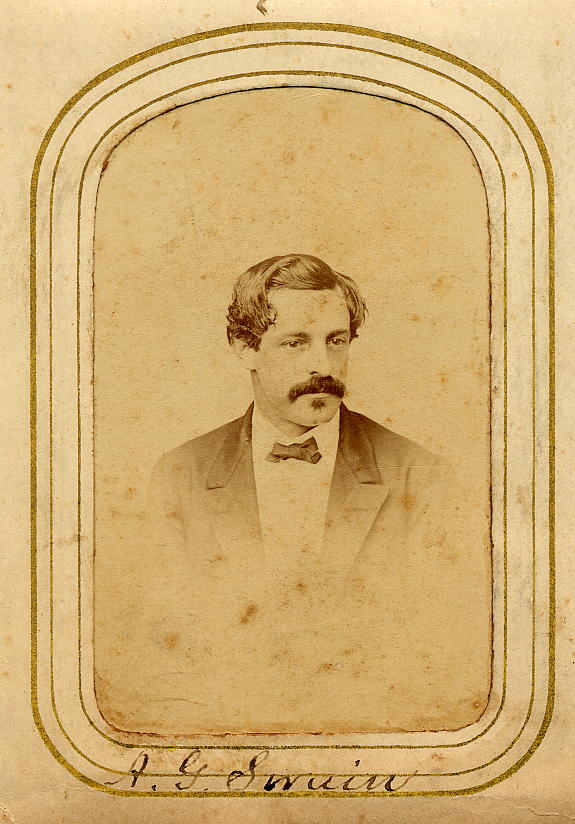

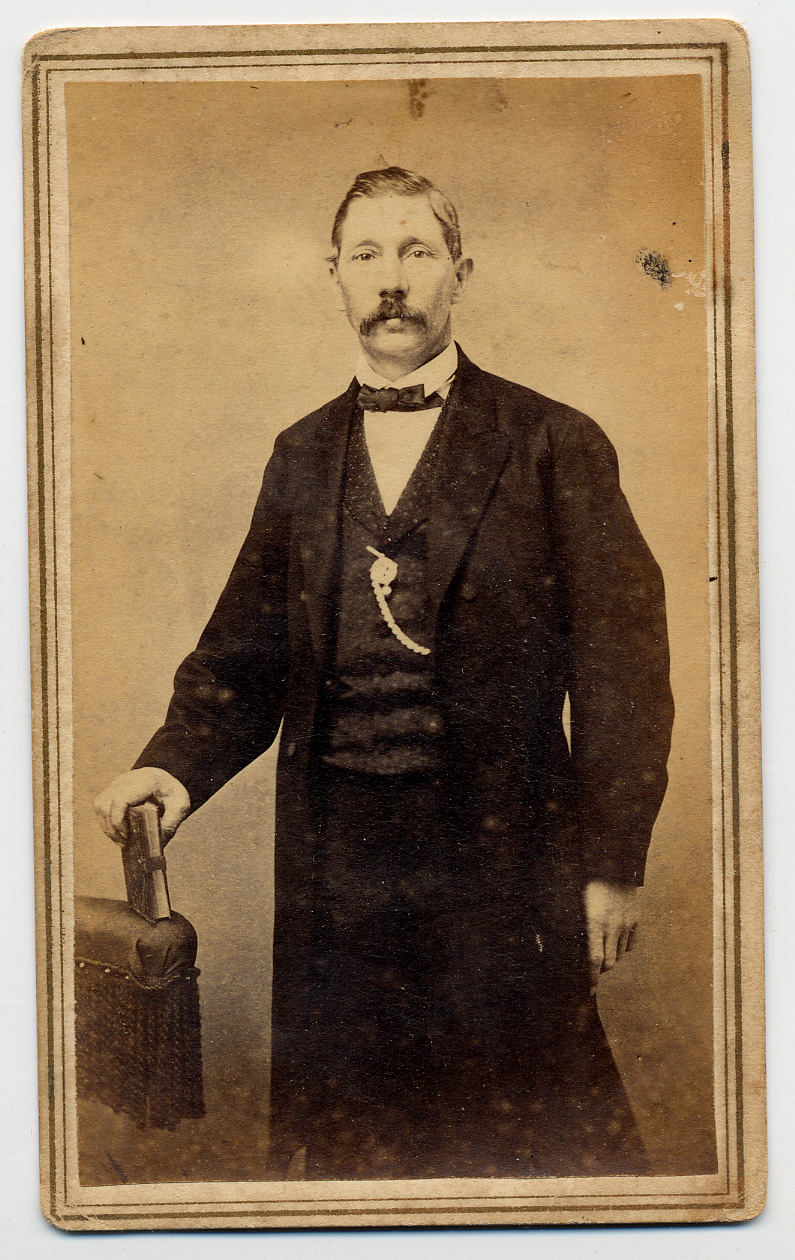

Andrew Gardner Swain

(Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, New

Orleans)

Andrew Gardner “Andy” Swain was born in Ohio but raised in New Orleans. Although he was a member of

the old Washington Battalion, he delayed enlistment with them for military

service in the Civil War until March 1862. This may have been due to his

employment as a riverboat pilot when he enlisted with the 5th

Company. He used that profession for the Confederacy in 1864 to transport

ordinance for General Richard Taylor.

Andrew Gardner Swain

(playing the guitar in cdv on right)

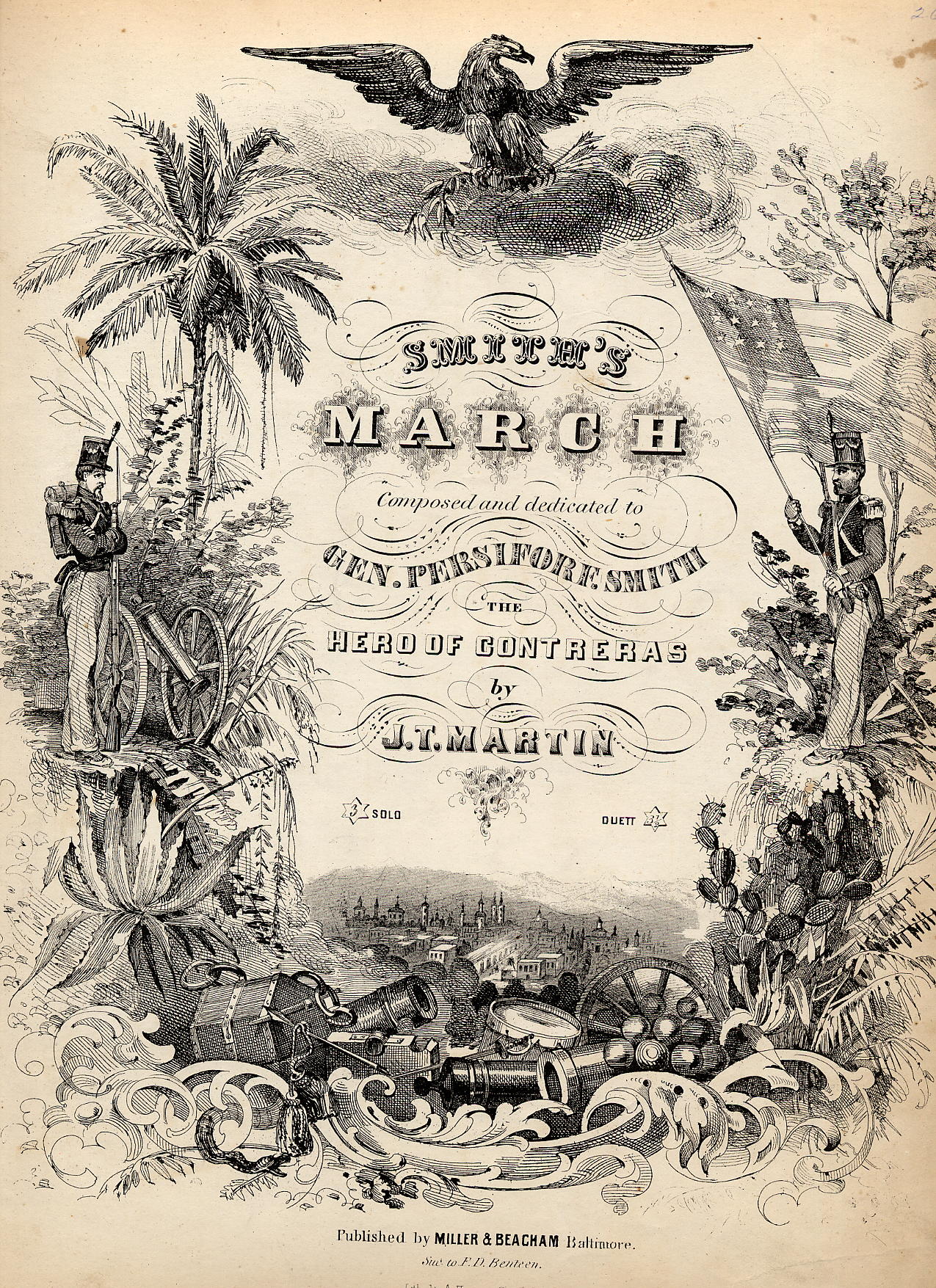

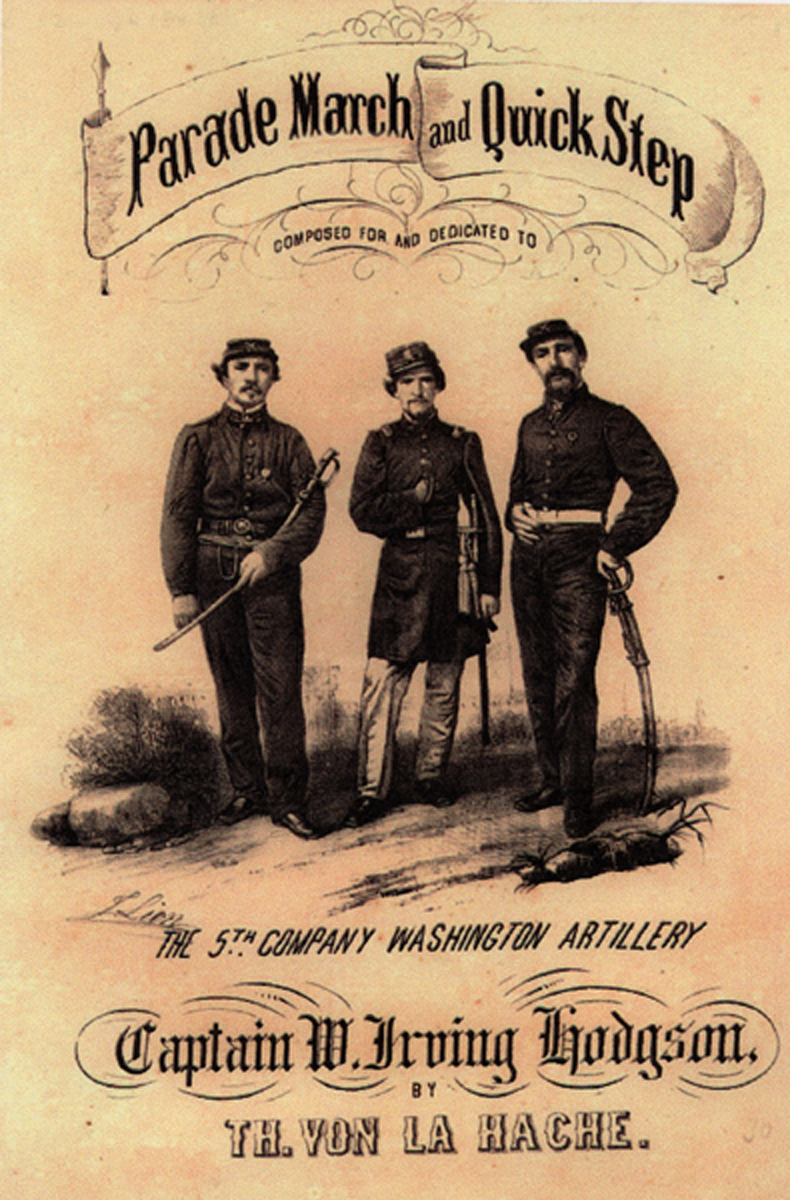

Washington Artillery Sheet Music

"Smith's March"

composed and dedicated to Persifer Smith

(Smith helped E. L. Tracy organize the

Washington Artillery in the 1840s)

by J. T. Martin

circa 1848

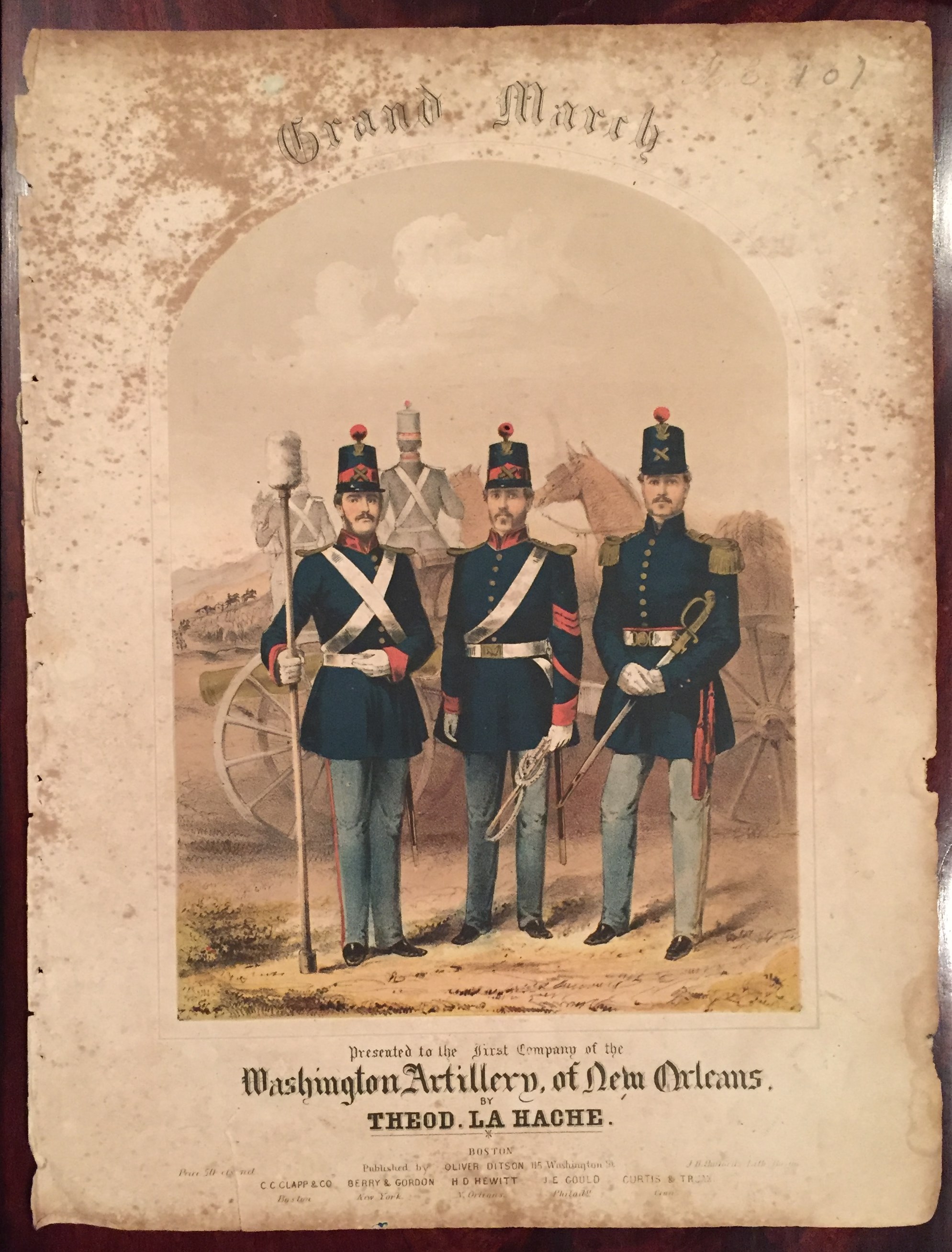

"Grand March"

composed by Theodore La Hache

circa 1850s

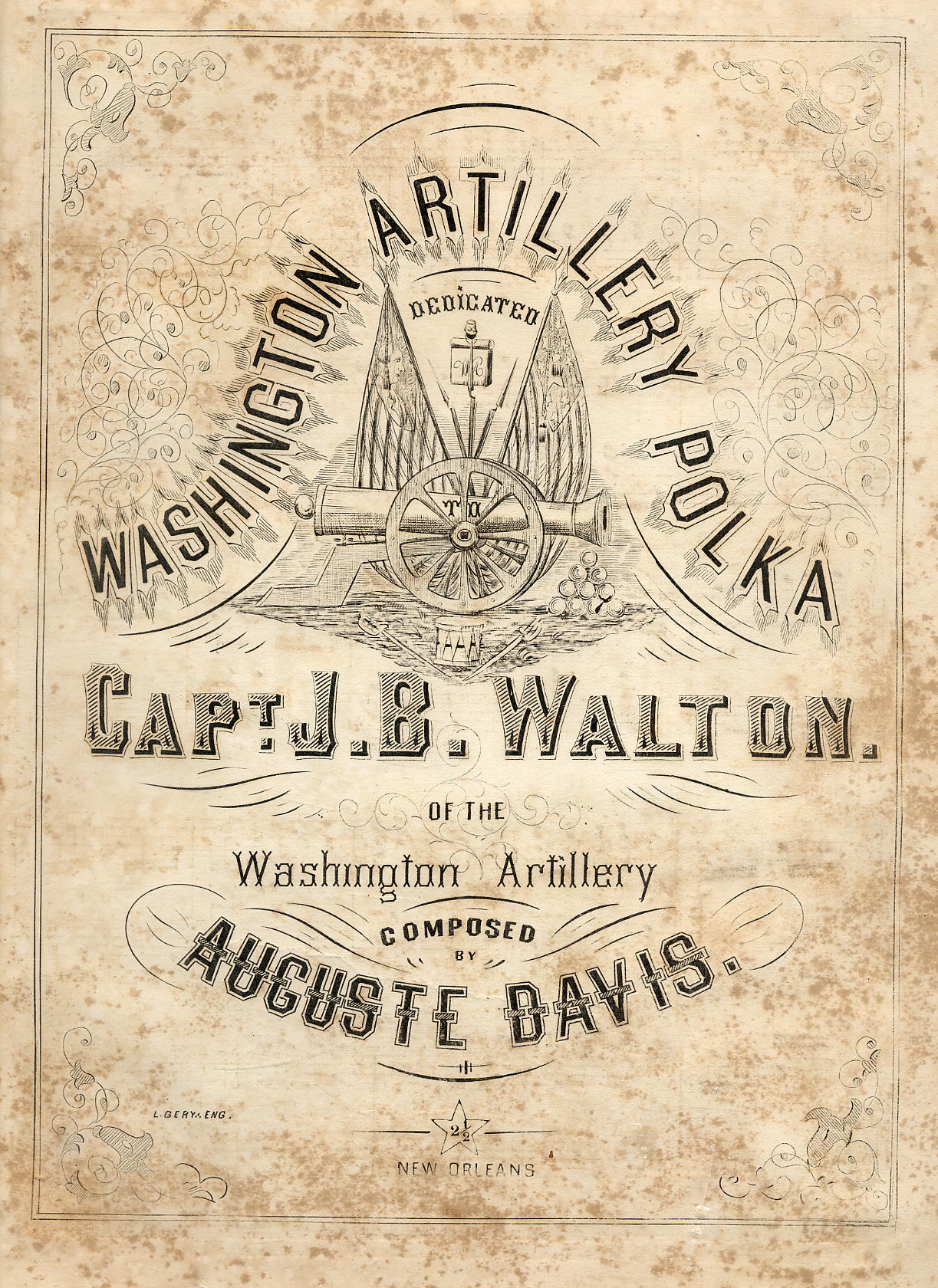

"Washington Artillery Polka"

by Auguste Davis

dedicated to Captain James B. Walton

circa 1861

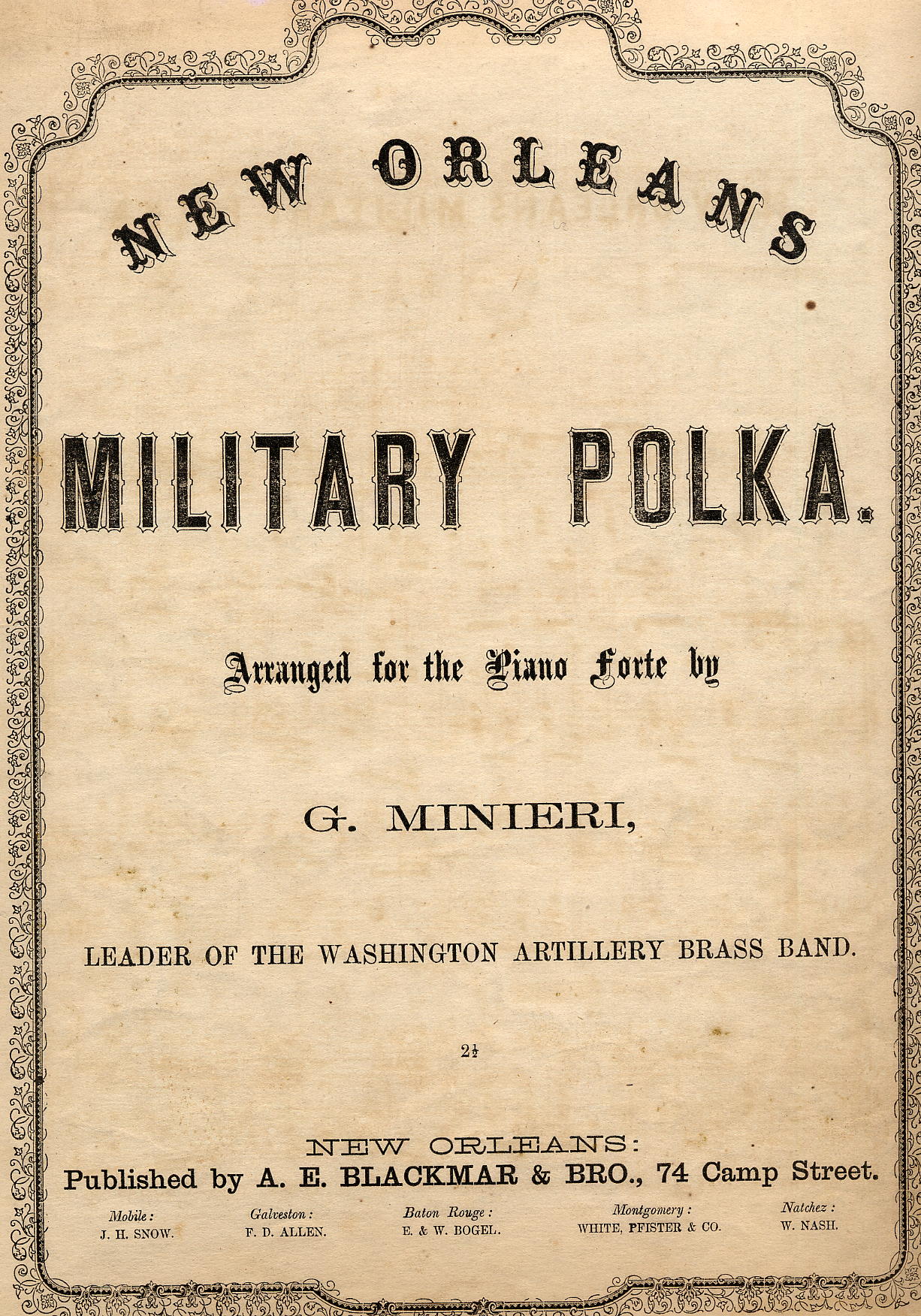

"New Orleans Military Polka"

by G. Ninieri, leader of the Washington

Artillery Brass Band

circa 1861

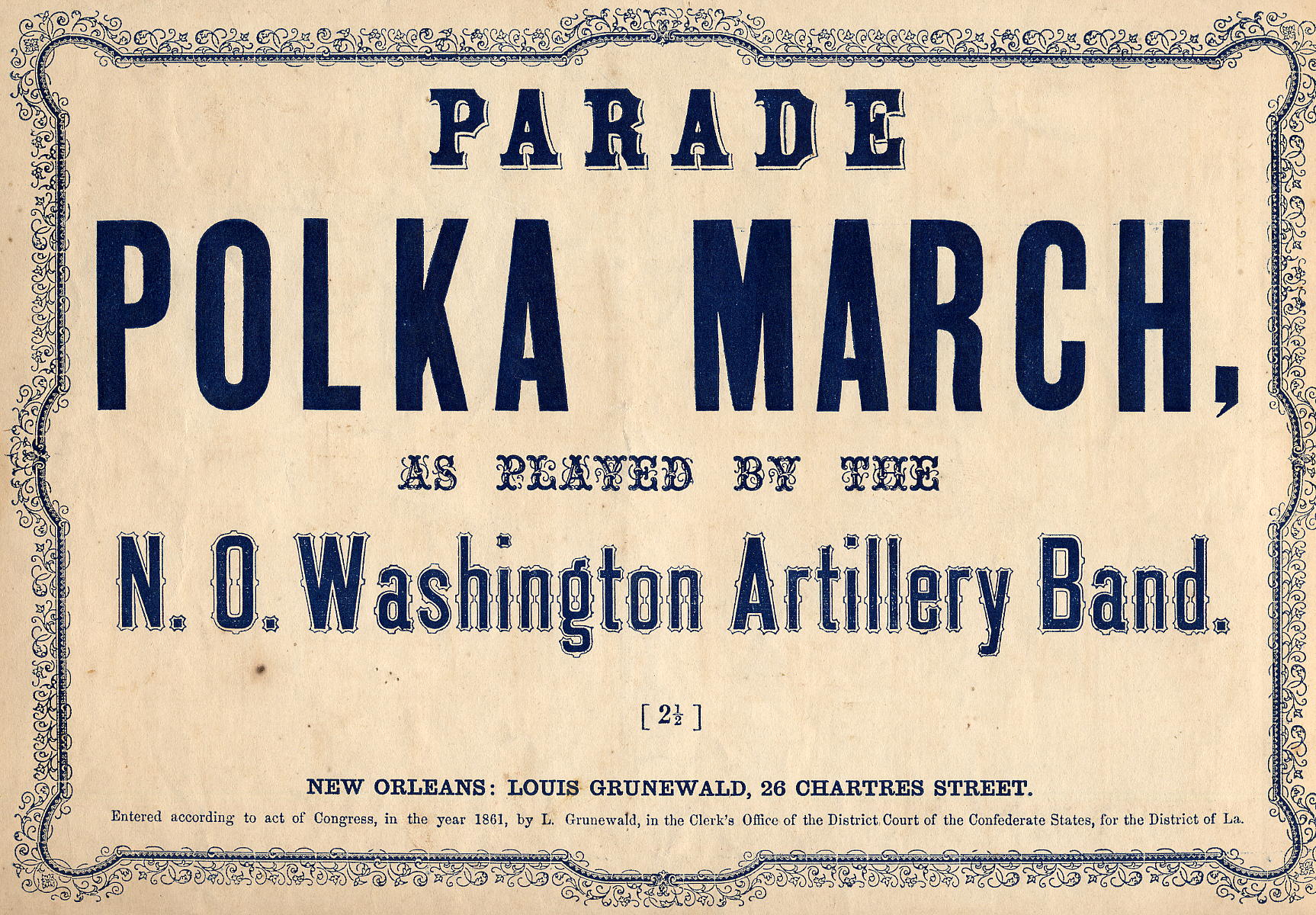

"Parade Polka March"

circa 1861

"Parade March and Quick Step"

circa 1862

New recruit Philip

Stephenson noted this aspect of the men of the 5th Company Washington

Artillery upon his transfer from an Arkansas infantry unit, “I found myself in

an altogether different atmosphere and among an altogether different type of

men. ‘Gaiety’ was the characteristic of these men-gaiety of spirit, talk, and

conduct, gaiety under all circumstances in camp, on the march, in battle,

freezing or melting, starving or stuffing, defeated or victorious.” “As to the

courage and reliability in battle or sharp emergency, … the battery boys would

go into a battle or come out of a battle with a song or a jest.”

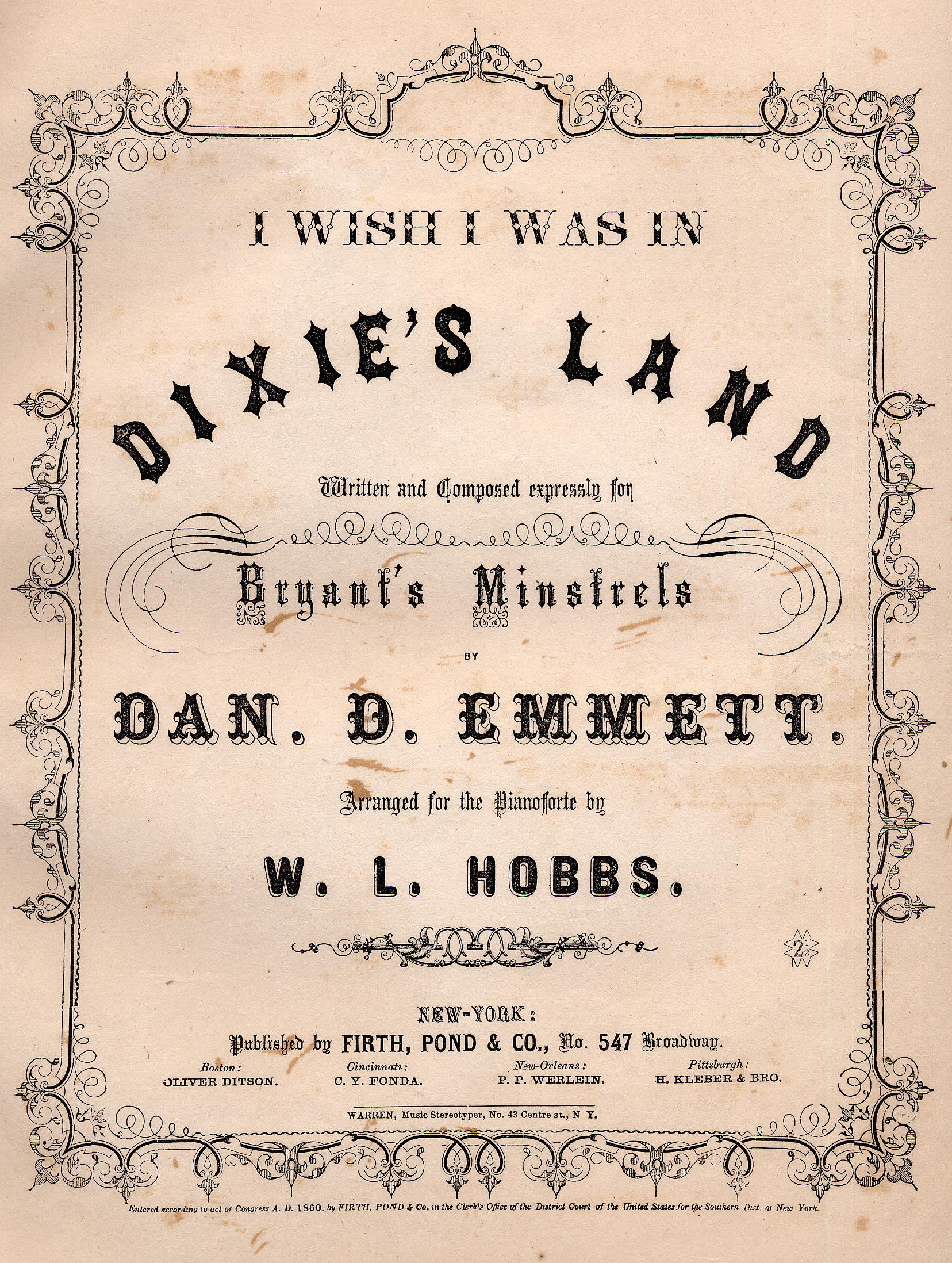

It

was Saturday night in 1859, when Dan Emmett was a member of Bryant's Minstrels

in New York. Bryant came to Emmett and said: "Dan, can't you get us up a

walk-around? I want something new and lively for Monday night." At that date all

minstrel shows used to wind up with a "walk-around." The demand for them was

constant, and Emmett was the composer of all the "walk-arounds" of Bryant's

band. Emmett of course went to work, but he had done so much in that line that

nothing at first satisfactory to him presented itself. At last he hit upon the

first two bars, and any composer can tell how good a start that is in the

manufacture of a tune. By Sunday afternoon he had the words, commencing: "I wish

I was in Dixie." This colloquial expression was not, as most people suppose, a

Southern phrase, but first appeared among the circus people of the North. In

early fall, when nipping frosts would overtake the tented wanderers, the boys

would think of the genial warmth of that section for which they were heading,

and the common expression would be, "Well, I wish I was down in Dixie" became

the rage. The tune was adopted by the Southern cause and became a national

anthem of sorts. The tune became a mainstay of the Washington Artillery band up

to and including World War II.

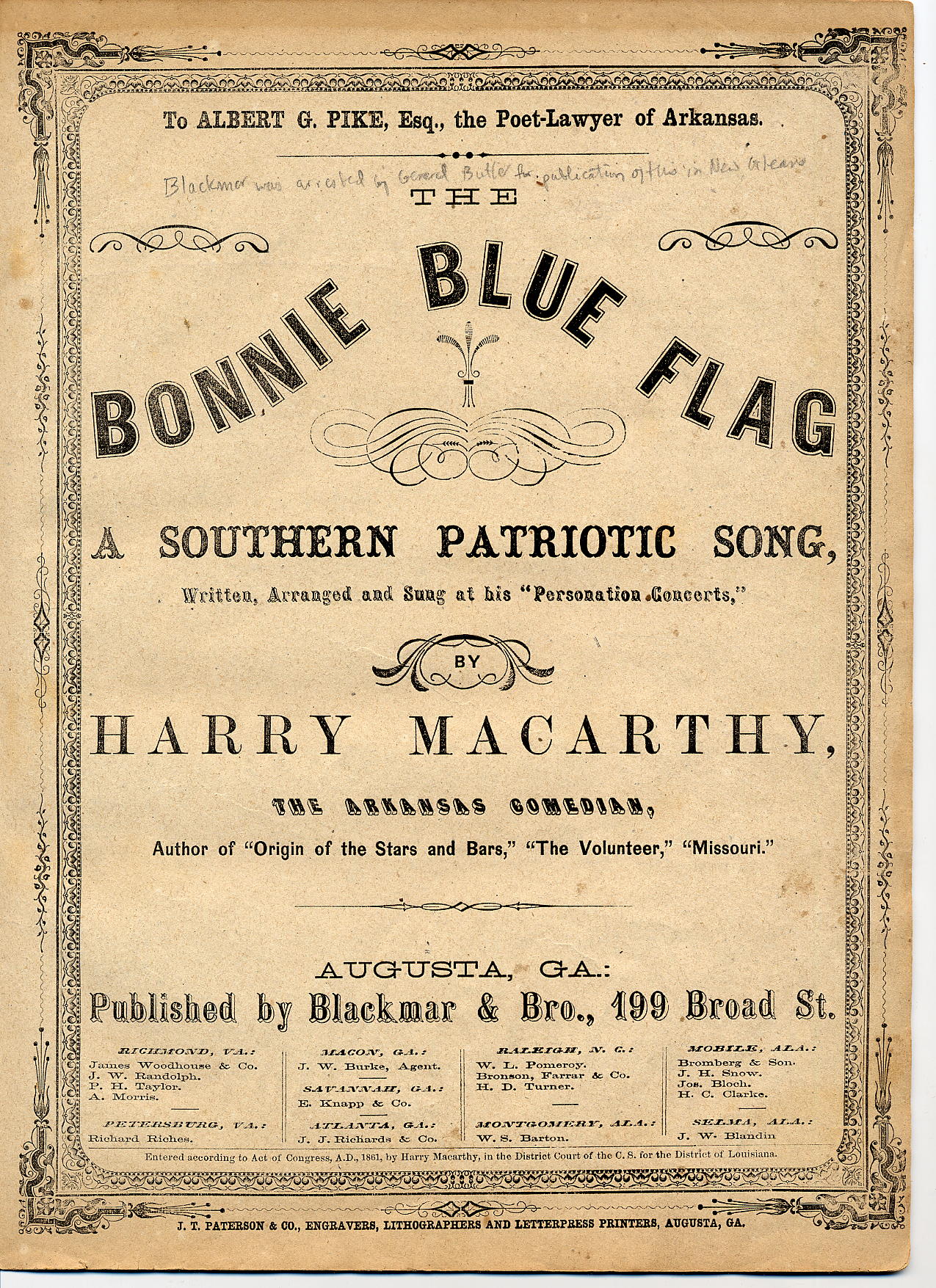

The “Bonnie Blue Flag” (also known as the "Lone

Star Flag") is often linked to the Confederacy. Although the flag had its

origins long before any southern state seceded from the Union (being the flag of

the Republic of West Florida in 1810), it was the “Lone Star” flag’s use by

Mississippi following that state’s first week of secession from the Union in

1861 that linked the flag forever to the Confederacy. Irish-born actor Harry

McCarthy witnessed the raising of the blue secession flag over Mississippi and

was inspired enough to pen a song entitled “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” linking the

flag forever to the Confederacy. When the song was first played in New Orleans

before a mixed audience of Texans and Louisianans, it was received with an

outburst of approval that was nearly riotous. The song became one of the most

popular songs of the Confederacy, second only to “Dixie.”

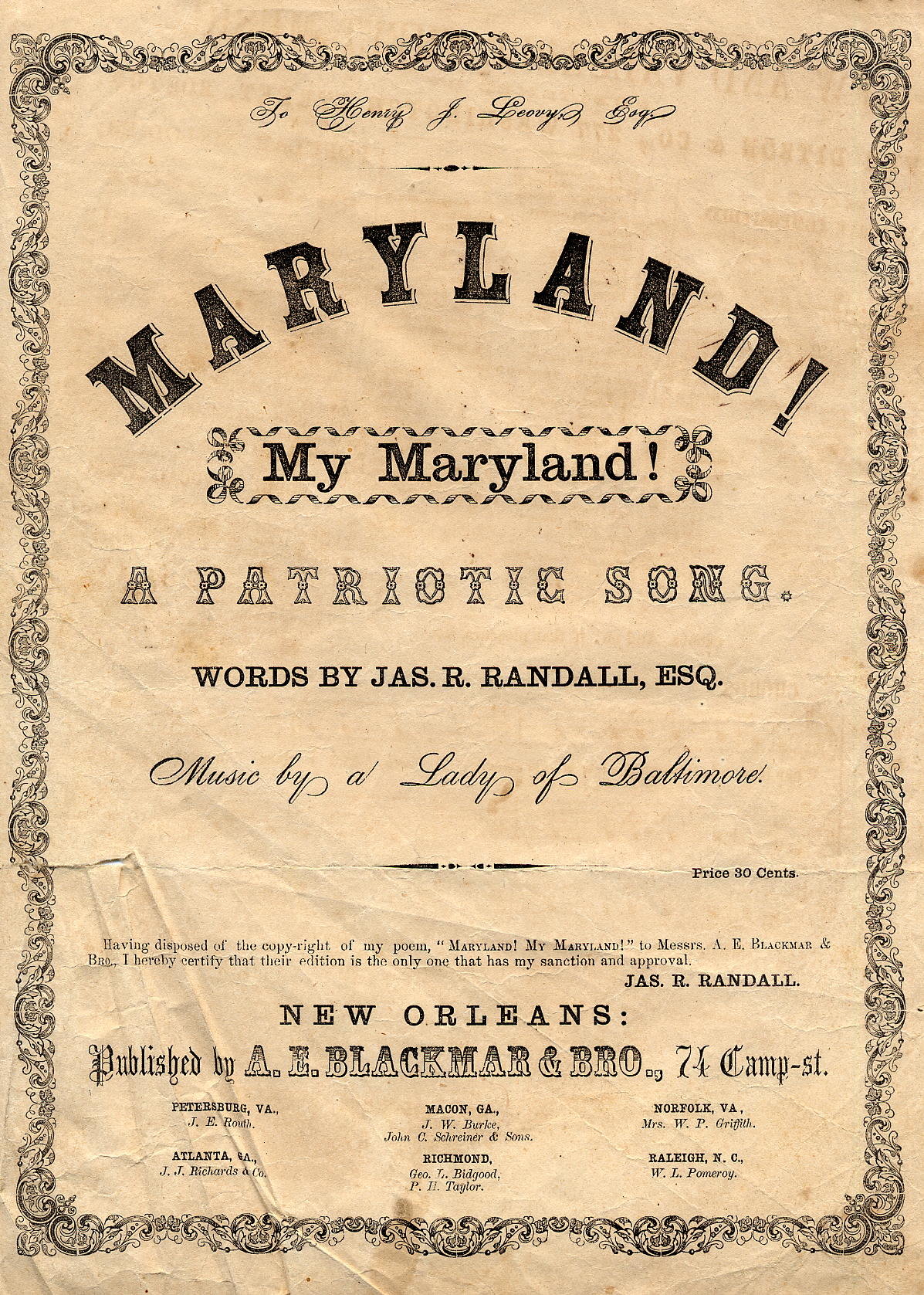

William Miller Owen also

mentioned the singing ability of his men. While in winter quarters after the

battle of Manassas, “the sparkling wit, the song, the anecdote, accompanied by

hot punch, that drove dull care away, and brought oblivion of the snow, the mud

and the rain outside. Can we forget? Never! Thomas Rosser, with his “Dragoon

Bold,” Isaac W. Brewer, with his “Maryland, My Maryland!” while “Old Bob Wheat”

would contribute a roaring chorus.”

Jennie Cary had set Randall’s stirring poem of “Maryland”

to the air of “Lauriger Horatius” and added “My” to help aid the

rhythm of the music. The song became a favorite of Confederate sympathizers and

soon echoed as one of the most famous of the Confederate battle tunes. Jennie

sewed one of the first presentation Confederate battle flags for the Confederate

commanders at Manassas, her work of art going to General P. G. T. Beauregard.

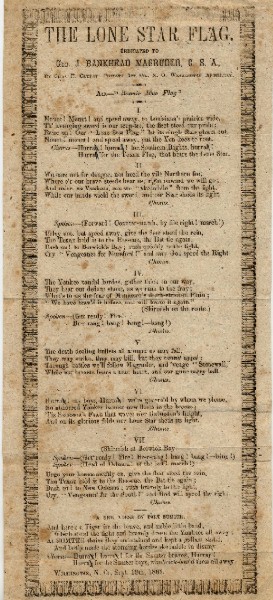

The Lone Star

Flag sheet music, sung to the tune Bonnie Blue Flag, was dedicated

to General J. Bankhead Magruder, C. S. A. and written by Charles E. Caylat, a

private of 1st Company. It was published on September 19, 1863 in

Wilmington, North Carolina. Caylat, a clerk turned driver, was age 24 when he

enlisted.

(image courtesy Confederate Memorial Hall Museum)

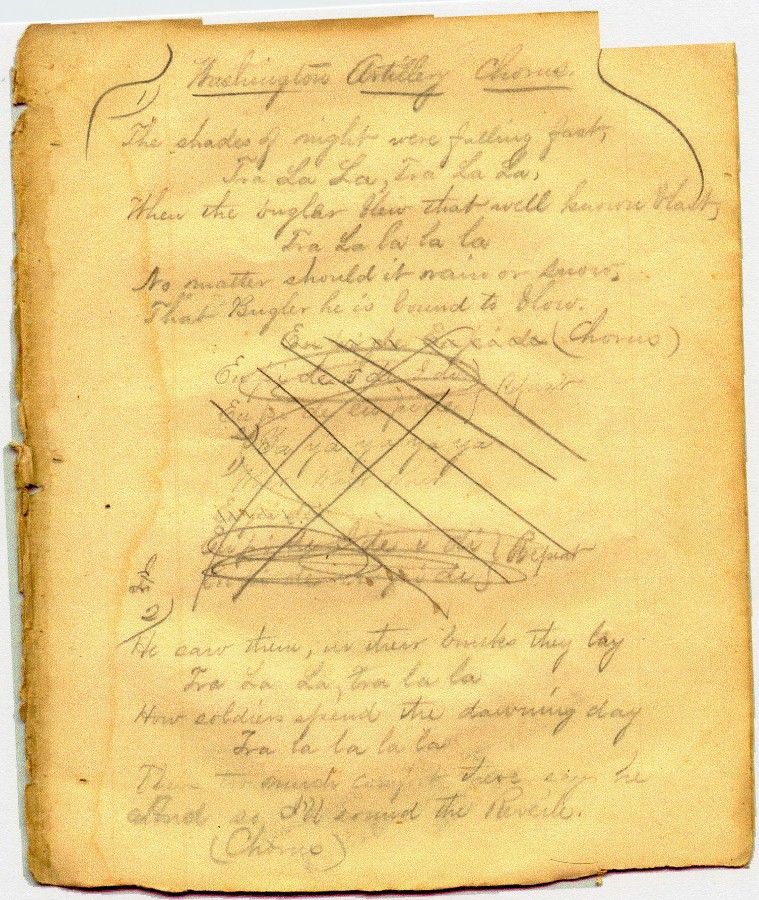

Frank Labrano of First

Company transcribed fellow member A. G. Knight's new lyrics to one of the most

popular Washington Artillery camp songs, "UPI-DEI-DI", in his diary seen

above. The “UPI-DE” song was probably

the most popular of the Washington Artillery camp songs. The melody was taken from

either an old

college tune or British army song. Washington Artillerist A. G. Knight

of Second Company made some additions and the men of the battalion sang it for the first

time in winter quarters in 1862.

Upi-Dei-Di!

The shades of

night were falling fast; Tra-la-la, Tra-la-la.

The bugler blew

his well-known blast, Tra-la-la-la-la.

No matter, be there rain or snow, that bugler still is bound to

blow.

Chorus

Upi-de-i de-i di!

Upi di! Upi di!

Upi de-i de-i di! Upi de-i di!

He saw as in their bunks they lay; Tra-la-la, Tra-la-la,

How soldiers spent the dawning day, Tra-la-la-la-la.

"There’s too much comfort there," said he,

"And so I’ll blow ‘The Reveille’."

On the fire he spied a pot; Tra-la-la, Tra-la-la;

Choicest victuals smoking hot; Tra-la-la-la-la.

Says he, "You shan’t enjoy that stew",

So "Boots and Saddles" loudly blew.

In nice log huts he saw the light, Tra-la-la, Tra-la-la,

Of cabin fires, warm and bright, Tra-la-la-la-la.

The sight afforded him no heat,

And so he sounded "The Retreat".

They scarce their half-cooked meal begin, Tra-la-la,

Tra-la-la,

Ere orderly cries out, "Fall in!", Tra-la-la-la-la.

Then off they march through mud and rain,

P’rhaps only to march back again.

Soldiers, you are made to fight; Tra-la-la, Tra-la-la.

To starve all day and march all night, Tra-la-la-la-la.

Perchance if you get bread and meat,

That bugler will not let you eat.

Oh, hasten then, that glorious day, Tra-la-la,

Tra-la-la,

When buglers shall no longer play, Tra-la-la-la-la.

When we, through peace, shall be set free

From "Tattoo," "Taps," and "Reveille."

A. G. Knight

in a post war cdv wearing his WA badge

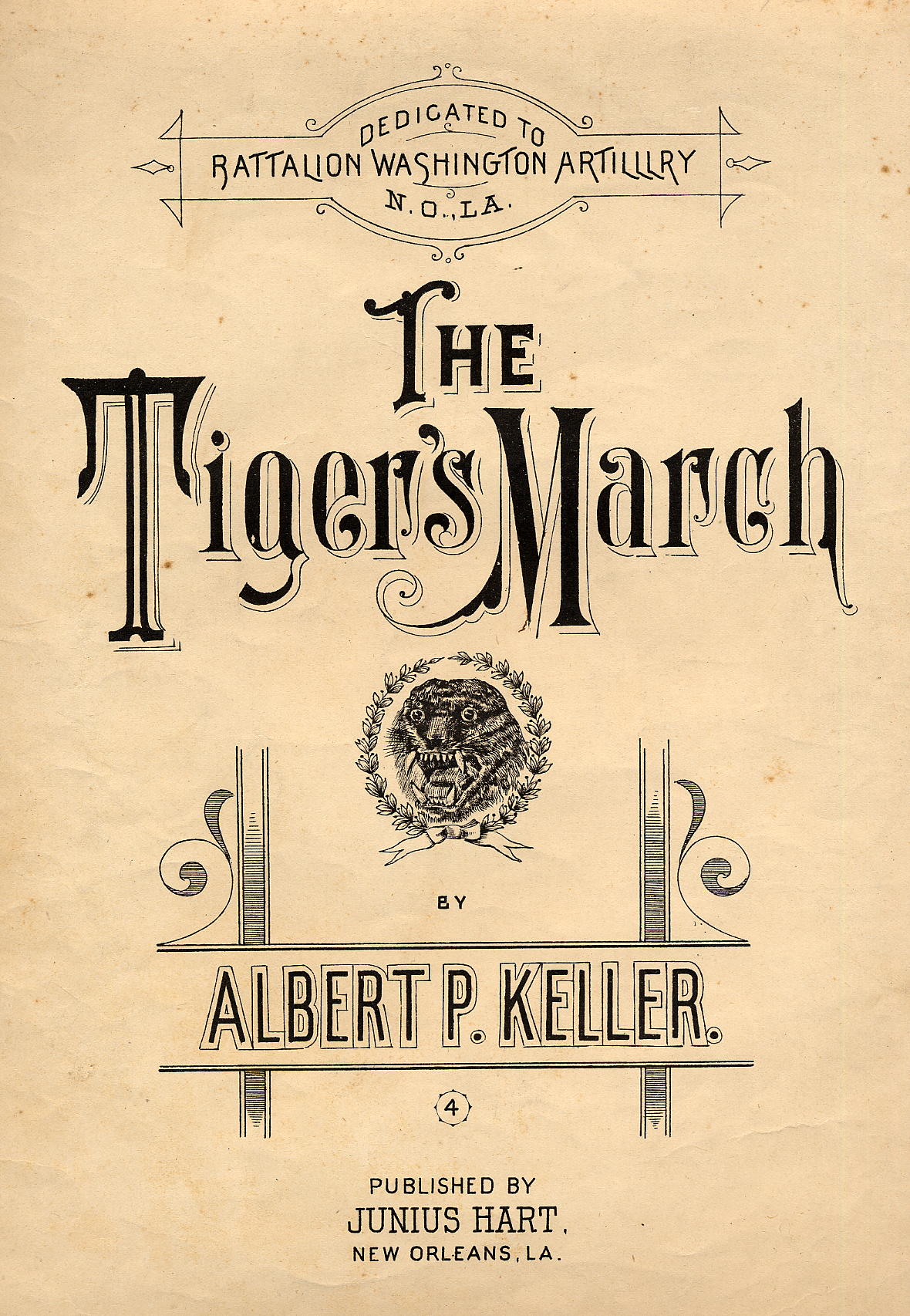

Washington Artillery Brass Band

circa 1880s

"The Tiger's March"

circa 1894

Battalion Washington Artillery

Lt. Col. J. B. Richardson riding his white

horse

with band parading down Camp Street, New

Orleans

(St. Patrick's Church can be seen in the

distance.)

circa 1890s

(photo courtesy John M. Fleming Collection)

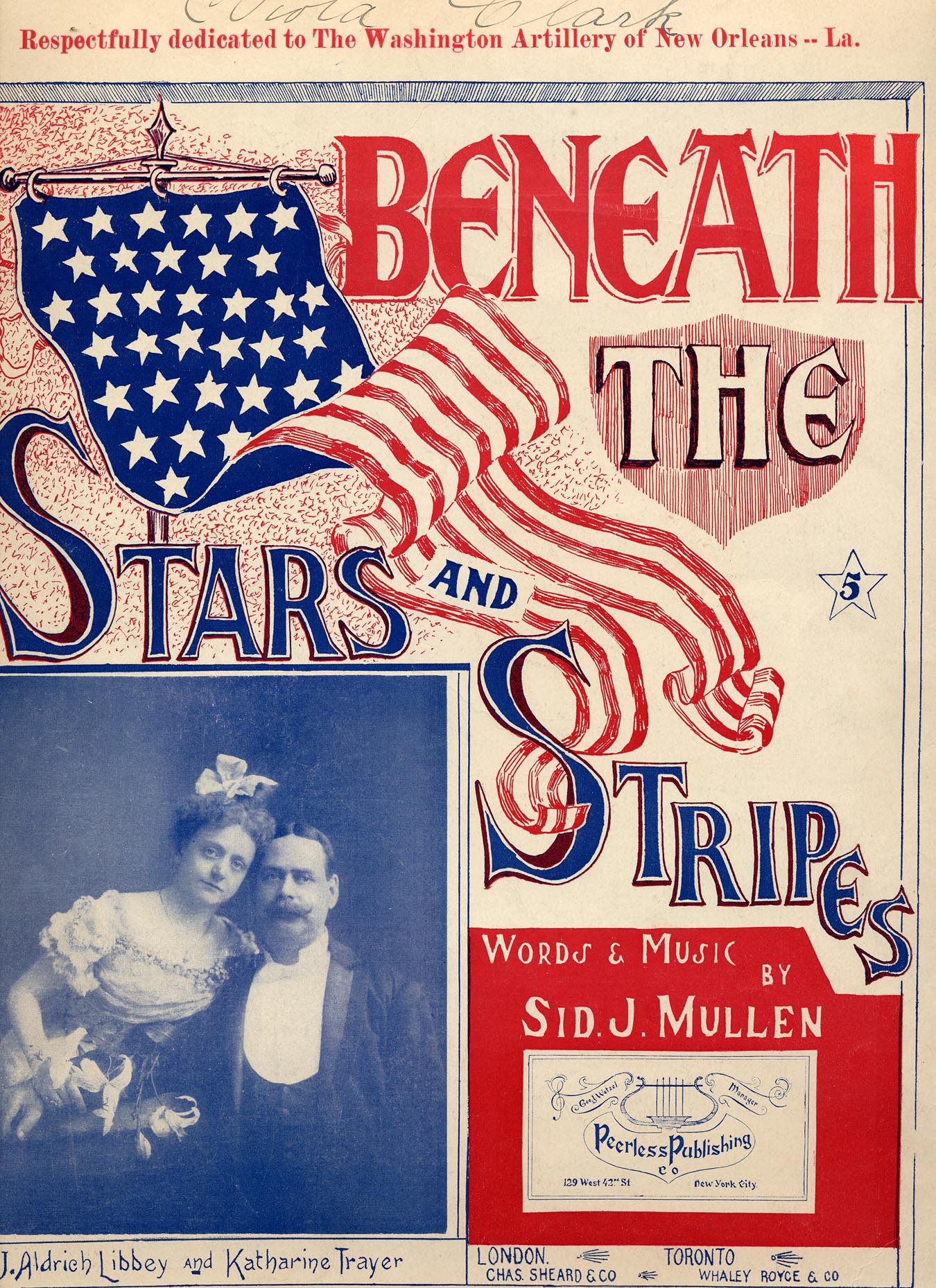

"Beneath the Stars and Stripes"

dedicated to the Battalion Washington

Artillery

by Sid J. Mullen

circa 1903

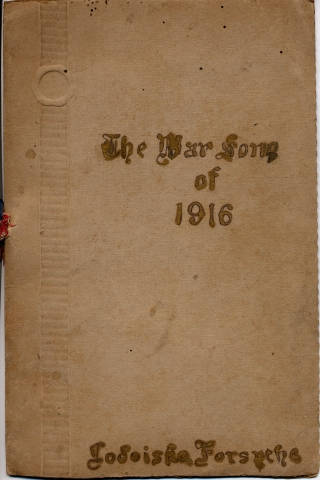

The War Song of 1916

Mexican Border Expedition sheet music dedicated to the Battalion Washington

Artillery

by Ledeiska Forsythe

Sung to the tune "Maryland, My Maryland!"

Its lyrics included, "To Mexico, to Mexico,

We'll join the fray at Mexico.

Our men are known in East and West/ Lads

from our land can stand the test.

Let's all unite and prove the rest/ For our

Country's name America."

(image courtesy Louisiana State Museum)

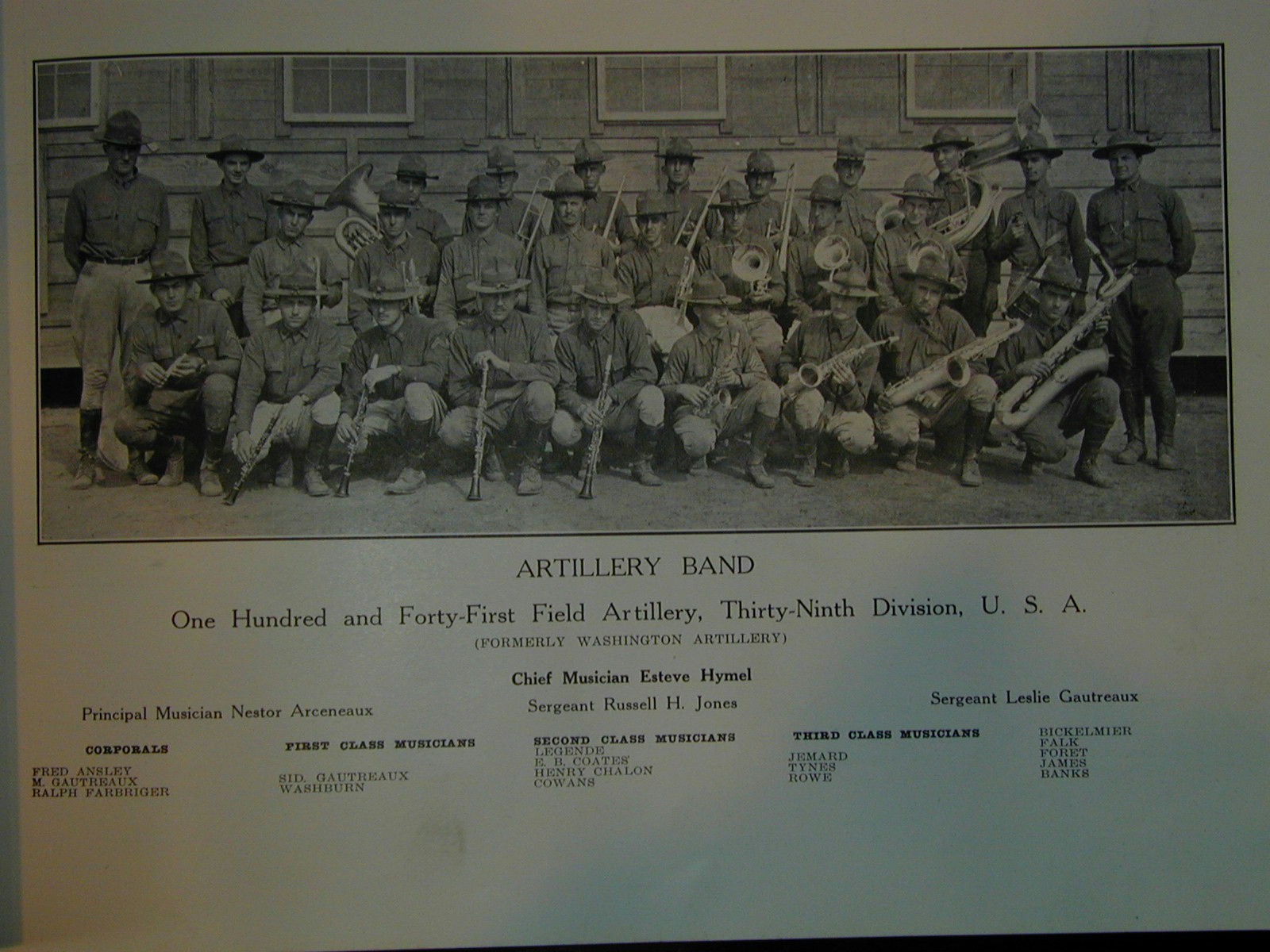

Washington Artillery Band - World War I

141st Field Artillery Song

(Washington Artillery Song)

1945

Played to the tune "I'm a Ramblin' Wreck

from Georgia Tech" the chorus sang,

"I'm a heluva, heluva cannoneer from the

141st, a heluva, heluva cannoneer from the 141st.

Like all good Field Artillery men I have a

heluva thirst, I'm a heluva, heluva cannoneer from the 141st!"

(image courtesy Louisiana State Museum)

more to come.....

(music:

Upi-Dei-Di!

performed by Echoes of Dixie)

Click on image for link

HOME